Who is a Filipino? Coming up with an operational definition for what makes someone Filipino is a thorny issue in the Philippine Basketball Association. But even outside of professional sports, developing a set of criteria someone must meet to be considered Pinoy is a classification nightmare. You're always going to omit someone who has a legitimate claim on identity.

Some readers of this blog have remarked that I'm becoming "Filipinized" the longer I live in the country. Should I ever be allowed to call myself Filipino, though? Perhaps if I renounce my American citizenship and emigrate permanently, but of the many ex-pats who make their lives here, hardly any are willing to kiss that blue passport goodbye.

To the PBA, a Filipino is a Philippine citizen with at least half Filipino blood. Filipino-Foreign players, however, are subject to a Byzantine set of eligibility requirements. It starts with team quotas. No team is allowed more than five Fil-Foreign players. Since these players are almost always Fil-American, I'm going to refer to them as Fil-Ams from now on, and the nitpicking fans of Australian Mick Pennisi and Tongan Asi Taulava will have to deal with it. Within a team's five Fil-Ams, only one can be half-Filipino. The other four must be foreign citizens whose parents were Filipino citizens living abroad at the time of their birth.

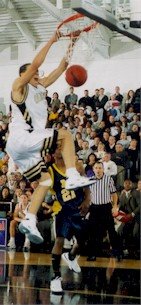

|

Fil-Tong Asi Taulava looking like Atilla from the Jean-Claude Van Damme film Lionheart. |

Stick with me here. This means that to play in the PBA as a Fil-Am, not only does one or both of your parents have to be "pure" Filipino, but they can't be naturalized citizens of your birth country when you are born.

Those rules only concern foreign players' ethnic backgrounds. There are also playing requirements Fil-Ams must fulfill in local college or semi-professional leagues before they can put their name into the PBA draft. If a foreigner transfers to one of the schools in the top collegeiate leagues like the UAAP or NCAA, he must wait two years before becoming eligible to compete in games. If a Fil-Am finishes college or junior college in the States, he is required to play 30 games in the PBA's feeder league, the semi-professional PBL. Only one Fil-Am is allowed on each PBL team, however, so there is a glut of foreign talent trying to fulfill their eligibility requirement so they can play.

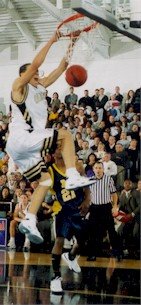

|

Golden boy Kelly Williams. |

Many of these guys live in Manila for a couple years, mooching off their buddies from home who've already made it to the league and relying on their agents for transportation and food money. But the leagues have all reached their saturation points for Fil-Ams under the current rules. Unless a recent arrival is a sure bet to be a star -- often this means he is at least 6'6'' with some Division I experience in the States -- like former Oakland University guard Kelly Williams, he may flounder and never make it onto a team.

It wasn't always like this. Fil-Ams were once the toast of Philippine basketball. Joel Banal, who coached Ateneo in the UAAP and Talk N Text in the PBA, said he thought the influx of Fil-Ams -- brash, exciting players with flashy, athletic moves -- rejuvenated Philippine basketball in the early 1990s. They brought the American game to the Philippines and forced local players to improve to remain competitive. Players like Vince Hizon, Mark Cagouia, Nic Belasco and Danny Seigle were fan favorites in their primes, with Cagouia and Seigle still playing major star roles for Ginebra and San Miguel Beer, respectively.

Ten years ago there was hardly any red tape to keep Fil-Ams from playing. Back then, foreign players could send a highlight reel of their best high school games to a professional team and have a fat contract of $5,000-$10,000 a month. Now, teams ignore them until they've proven themselves to be potential stars.

|

When you say Fil-Am out here, this is the kind of image that comes to many people's minds. |

There are several reasons for the 180-degree turnaround in attitudes towards Fil-Ams. First, they have a repuation for bad behavior. The word that gets tossed around in relation to them most often is

mayabang, Tagalog for arrogant, but with a little more kick. Fil-Ams are reputed team killers, cocky Americans who disrespect their coaches, teammates and league officials. They dress like American basketball players -- long shorts, baggy clothes, chains, du-rags, etc. -- and they're seen as uncontrollable thugs, whether or not it's true. The Philippines, despite its renowned Western influences, remains very Asian in that individuals are expected to defer to groups. Getting along well is such a deep value that many people would rather lie than say something that might make someone else upset. So when a fresh Fil-Am hops off the jet from Los Angeles, makes his teammate fall with a crossover, laughs at him and asks, "Why you even trying to guard me, stupid?" he won't be ingratiating himself with the locals.

The bad behavior extends beyond the basketball court. Once again, Fil-Am players may not deserve this reputation, but they're said to party too much, start fights and act extremely sleazy with local women. It's true that a lot of foreign ballers have multiple girlfriends, mistresses and lovechildren. However, it wouldn't take long to find local players who are into similar dirt. In fact, extramarital philandering is so common here that in a recent poll cited in the August 14 issue of

Newsbreak, a majority of teenagers said cheating on a boyfriend or girlfriend was "outright wrong" while 60 percent of them saw nothing wrong with cheating on a husband or wife. Former Senator Ramon Revilla, Sr., is reputed to have roughly 80 illegitimate children, and he's often complimented on the fact that he supports them financially.

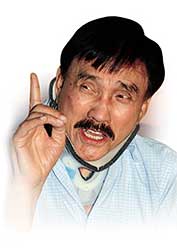

|

Say what you will about Ramon Revilla, Sr., but the man certainly knows how to sire children. |

The difference between Fil-Am philandering and pure Filipino womanizing is that locals know the "right" way to be sleazy. I'm sure I just lost all 4 of my female readers, but for better or for worse, certain kinds of infidelity are accepted in Filipino culture. Mistresses should be kept out of sight and away from the family, but it's accepted and sometimes expected to lavish them with gifts, apartments and affection. I wouldn't call all these relationships discreet, but neither are they crass. Everyone plays their role and does their best to save face. But Americans don't get down like that. We ain't about living a lie and saving face, we keep it real! So the foreign ballers who pick up girls at clubs like Embassy and Jaipur, take them home and send them on their way an hour later with their boots smoking are doing it all wrong. It's like there's an agreement between a mistress and her man -- she'll accept the unequal relationship if he treats her nice when they're together and gives her some goodies now and then. But Americans tend to be strictly hit-and-split, and that hurts their reputation with the fans, which is possibly worse for their careers than the bad rap they get with teams. The PBA is basketball as entertainment, modeled after the NBA, and if the masses are sick of Fil-Ams, then the league has no use for them.

But although the players are no angels, I still see problems with the PBA's racial guidelines. Compare two recent PBA draftees, Kelly Williams and Gabby Espinas. Both have Filipina mothers and African-American fathers. Espinas was raised in Olongapo City near the old U.S. naval base at Subic Bay. Williams was raised in Detroit, Michigan. According to the PBA, Espinas is a Filipino and Williams is a Filipino-American. Williams is fortunate. Because he's a 6'6'' wing player with Division I experience at Oakland University in Detroit, any PBA team would figure out a way to fit him into their roster, even if it meant cutting another Fil-Am. A less heralded U.S. recruit with Williams' ethnic makeup -- even one as good as Espinas, the fifth pick in the draft -- might be passed over by teams that don't want to deal with the trouble of juggling the Fil-Ams on their rosters.

The idea of safeguarding the Filipino bloodline is absurd at this point. "Pure" Filipinos had mixed with Malays and Chinese even before the Spanish arrived in the 16th Century. Those frisky Spaniards made their fair share of babies, and several prominent Spanish families still run big businesses in Manila. Americans supplanted the Spanish rulers in the 20th Century and brought English, Hollywood, basketball, public education, a form of government that resembles democracy and the U.S. armed forces to the island. Add all the foreign invasions and influences up and you get one extremely mixed ethnic heritage. If the PBA really wants pure Filipinos, they'll have to reach deep into the indigenous peoples of Mountain Province of Northern Luzon or the Muslim minorities in Mindanao to find the groups least touched by the colonialists.

|

The Kalinga Headhunters' starting point guard. |

While I admit there's a certain charm to the idea of an Igorot versus Aeta hardcourt grudge match or a Moro versus Kalinga game 7, the quality of the basketball might leave something to be desired. Watching the tiny, hunter-gatherer Aetas hack away at the g-string clad Igorots, neither of them having any idea what to do with a basketball, might be humorous for a while but it's not something I'd want to watch for two hours. And the Kalinga, renowned headhunters, could present a serious court management problem for referees.

While I understand the PBA's desire to please local fans by featuring truly Filipino players, the league's attempt to codify Filipino ethnicity strikes me as arbitrary and misguided. I say let the teams decide what kind of players they want to suit up, whether it be Fil-Ams, Tsinoys (Chinese Filipinos), Visayans, Ateneans, indigenous peoples or whatever mix of basketball players wins games for them.